Writing for bowed cymbals

Luigi Marino, 2010 (rev. 2025)

Notes about the 2025 revision

After more than fifteen years since I first marked pitches and multiphonics on my cymbals, I decided to revise this writing in conjunction with the release of my recent solo work devoted entirely to bowed cymbals. Although the core of the technique has remained consistent, the latest mappings have revealed many more possibilities and details I hadn’t noticed before. From the initial surprise of being able to write actual pitches for bowed cymbals, to later adding a just-tuned interval above a fundamental by using a second bow on the same cymbal, a great deal has changed in how I understand the order hidden inside these metal instruments.

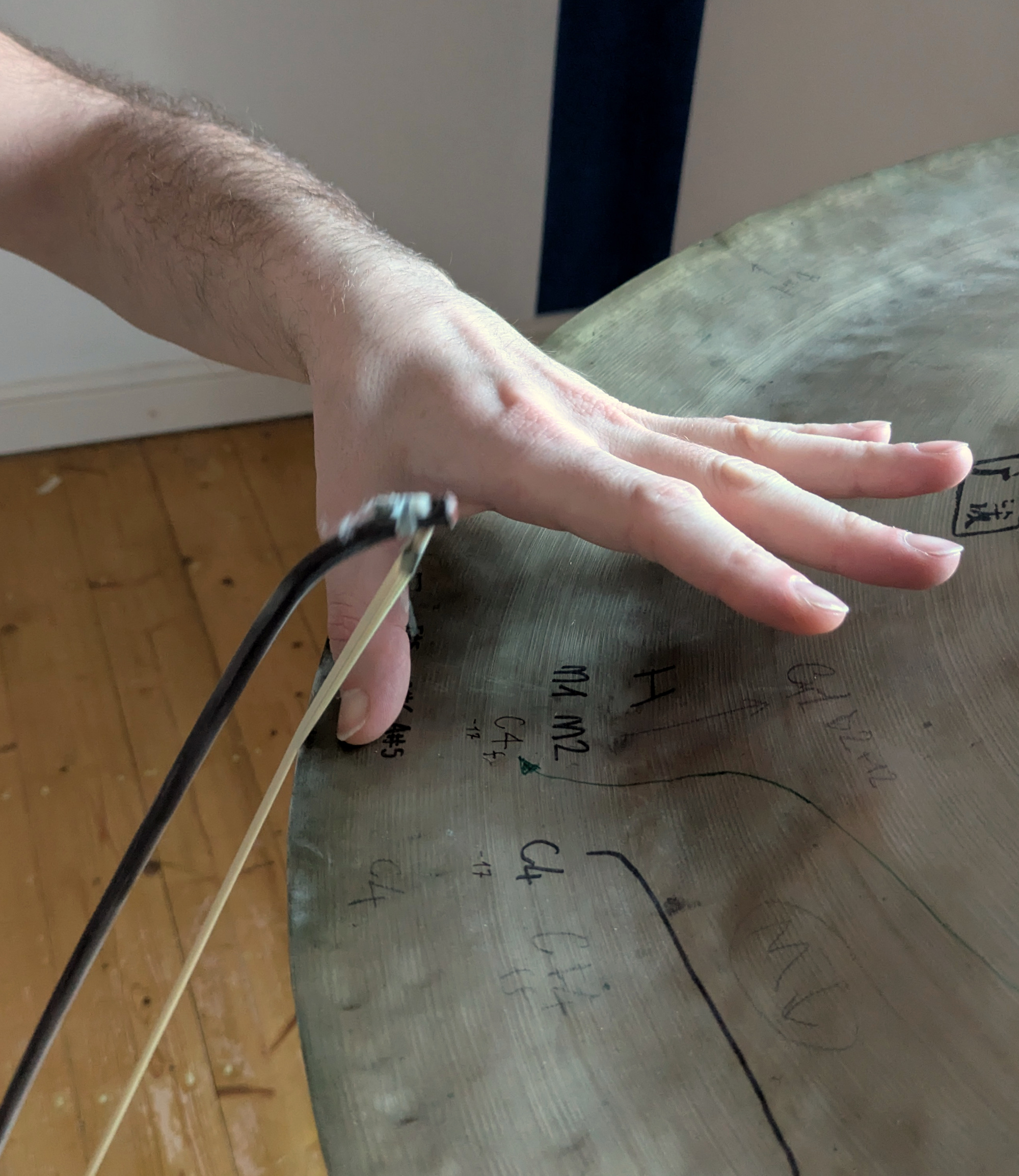

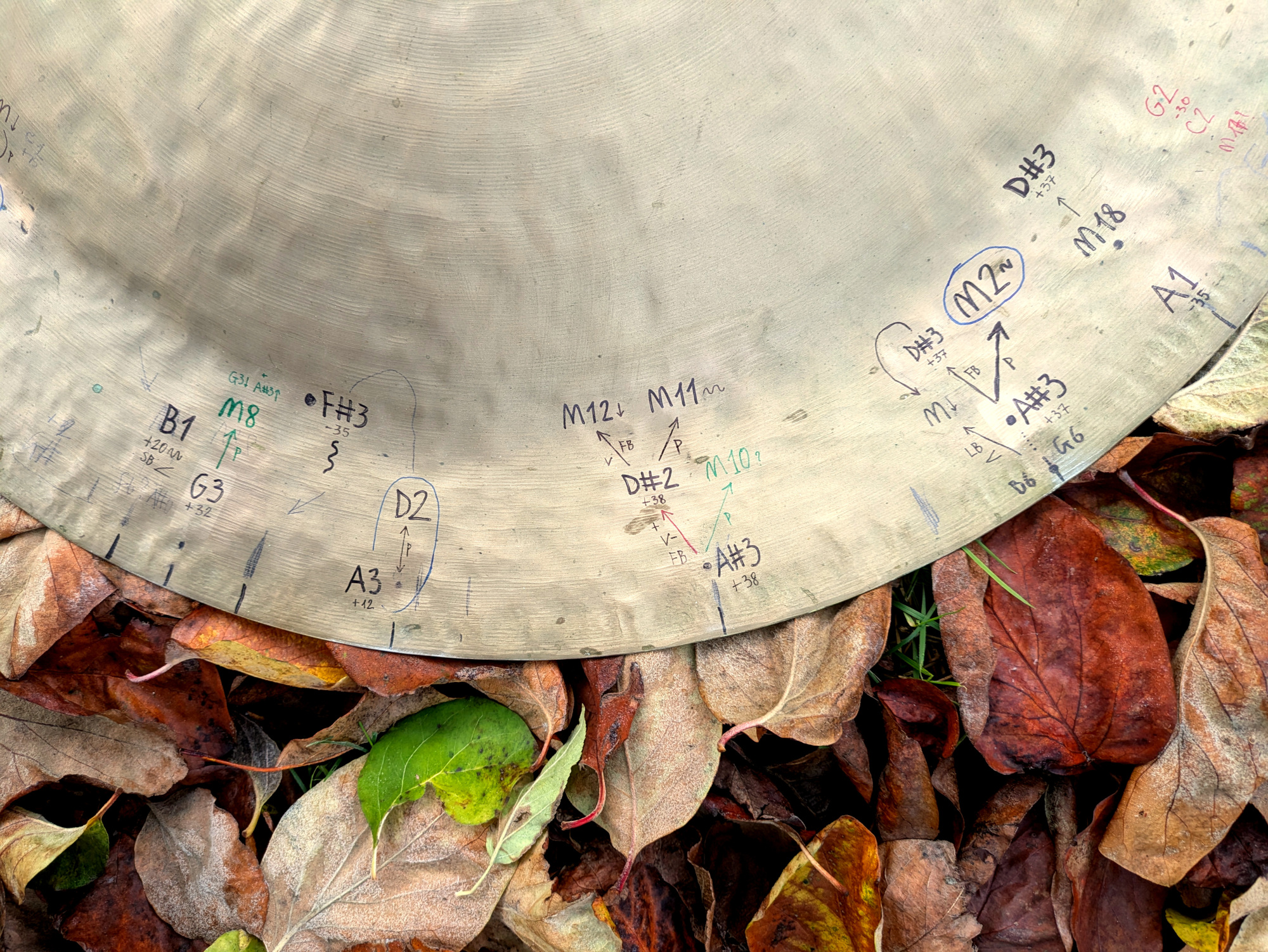

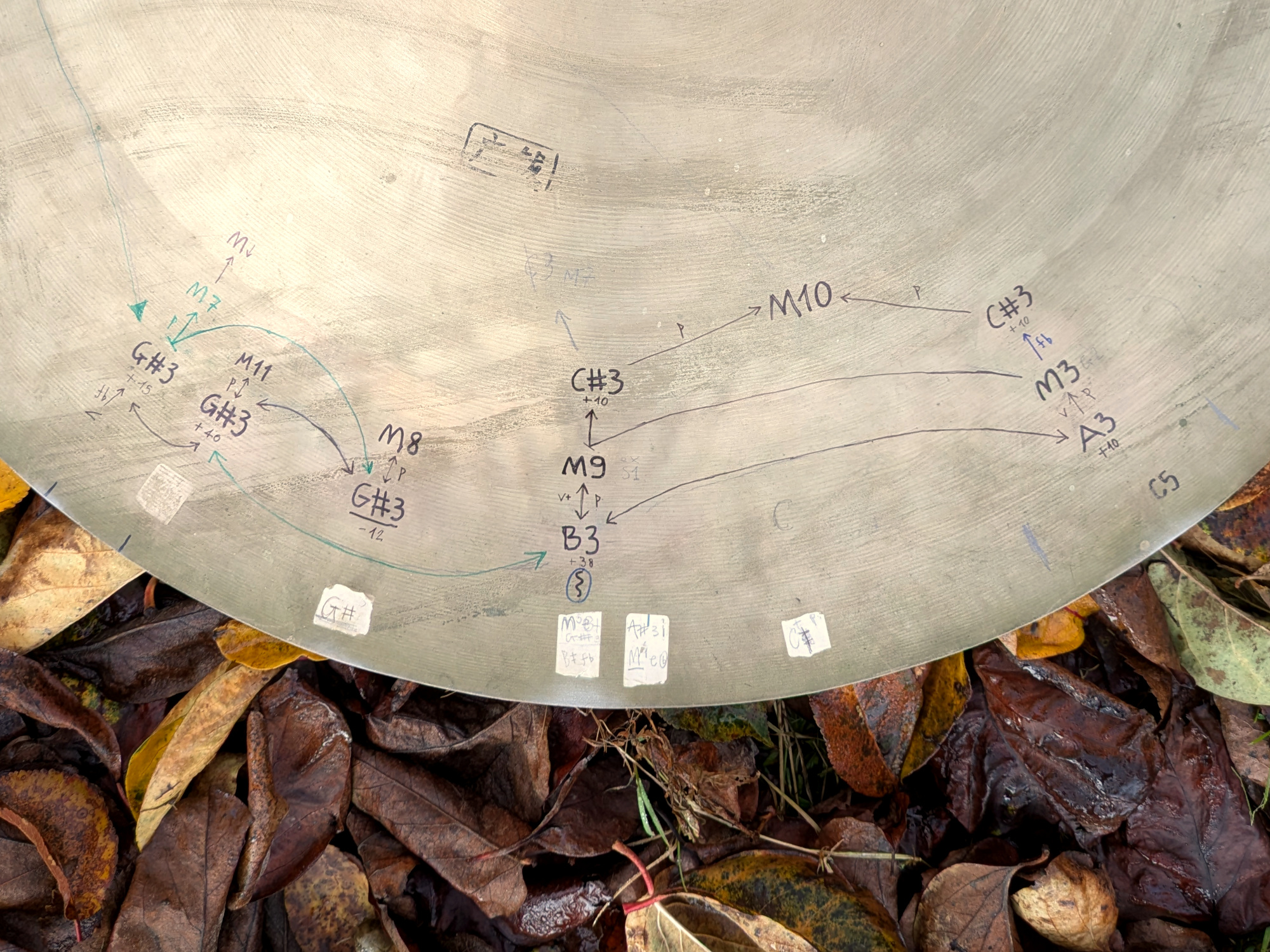

The idea of mapping sounds on cymbals first came up during a series of improvisation sessions in which I began noticing recurring sonic patterns while bowing them. Around the same time, I had the opportunity to write for a small chamber group that included three percussionists, and in order to provide some written material, differentiate the parts, and communicate both the ideas and the techniques within the ensemble, I started a more systematic analysis of the instruments. The initial findings were limited, but the markings have since grown considerably (see pic. 6).

In this new version, I’ve added updated examples, including samples from my recordings and photos of some of the most interesting areas of the mappings, each paired with audio demonstrations.

I’ve also learned about several early uses of bowed cymbals and gongs by other musicians, and I’ve added some of those references here to give a clearer picture of what was happening before I began working on this technique. Since I’m a musician based in Europe, the examples I know are inevitably shaped by geography and by the network of people I play with. If you know of early documented cases I’ve missed, please get in touch and help me correct my bias, but only verifiable sources, and categorically no national-superiority nonsense: with the way things are going at the time of this revision, I ran out of patience for anyone trying to invent a narrative just to claim that people who share their native language or appearance were influential.

Brief historical considerations

Bowing cymbals is a well-known technique and appears regularly in both contemporary written music and free improvisation. The earliest use I could find in notated music is in the fourth movement of Arnold Schoenberg’s Fünf Orchesterstücke (1909), where the cymbal part calls for a tremolo using a cello bow. By the 1950s, the technique was already familiar to Hollywood sound designers, who used bowed metal to create eerie or otherworldly effects.

In 1964, Mario Bertoncini wrote Quodlibet for viola, cello, double bass, and percussion, where the bowed cymbal is treated not as an effect but as a primary sound source. In this piece, Bertoncini also introduces a specific method for producing high pitches on the cymbal. When he joined the Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza in 1965, he brought this metal percussion work into the ensemble’s shared vocabulary.

Around the same time, at the very beginnings of what would later be called free improvisation, the bow starts becoming a standard tool for playing metal percussion. It appears on early recordings by members of MEV, in Tony Oxley’s work (e.g., the track Oryane from the album Ichnos), in Eddie Prévost’s playing with AMM1, and even in some early archival photos of Carl Palmer from the first years of Emerson, Lake & Palmer.

By the 1990s, many percussionists working in experimental music—both composed and improvised—were using bows to excite cymbals and gongs. They include William Winant, Lê Quan Ninh, Günter Müller, Michele Rabbia, Burkhard Beins, Michael Vorfeld, and Christian Wolfarth, who has worked extensively with bowed cymbals since the early 1990s and has released solo cymbal works in which bowed cymbals play a prominent role.

Other compositions featuring bowed cymbals or bowed gongs include Tune (1965) by Mario Bertoncini, likely the first piece written entirely for cymbals; Asterism (1968) by Toru Takemitsu; A Haunted Landscape (1984) by George Crumb; and Immersion (1998) by Annea Lockwood.

The sounds produced by bowing a cymbal are not easy to control, and it’s not surprising that the technique has been used most often for orchestral effects, ambient or atmospheric music, indeterminate compositions, and free improvisation. In the orchestral tutti of Fünf Orchesterstücke, the cymbal’s bowed sound blends into the overall timbral gestalt; in Quodlibet and Tune, the unstable partials of the cymbals are treated as primary material, aligned with the aesthetics of the informal art current. The same is true in many improvised settings.

What follows is an attempt to define a set of techniques that might be useful to improvisors interested both in the unpredictability of these sounds and in being able to make deliberate choices about which sound to play, and to composers in need of a more deterministic approach. It is also for anyone fascinated by the experience of finding sounds and recurrences on instruments that come as a blank sheet, whose relationship between gesture and sound can be discovered, as far as I know, only through practice and attentive listening.

Mapping sounds on a cymbal

Pic 1 - A Wuhan cymbal measuring 68cm in diameter after the mapping

Pic 2 - Same diameter and similar shape but completely different set of sounds

The cymbals I used most measure 68 cm in diameter (pics 1 and 2) and were handmade in Wuhan, China. They are more commonly found as Wuhan cymbal 27" or China Cymbal 70. The fact that they are handmade is very important, because the irregularities of the metal contribute significantly to the variety of sounds one can find on them2. If the cymbals are sufficiently irregular, then even with the same diameter each new mapping will produce a completely different set of sounds and relationships. The irregularity of the rim is one of the main factors influencing this variety: a thicker rim tends to produce lower pitches, likely because a larger area is excited by the bow (see pic. 3), but I could not find precise correlations and exceptions abound.

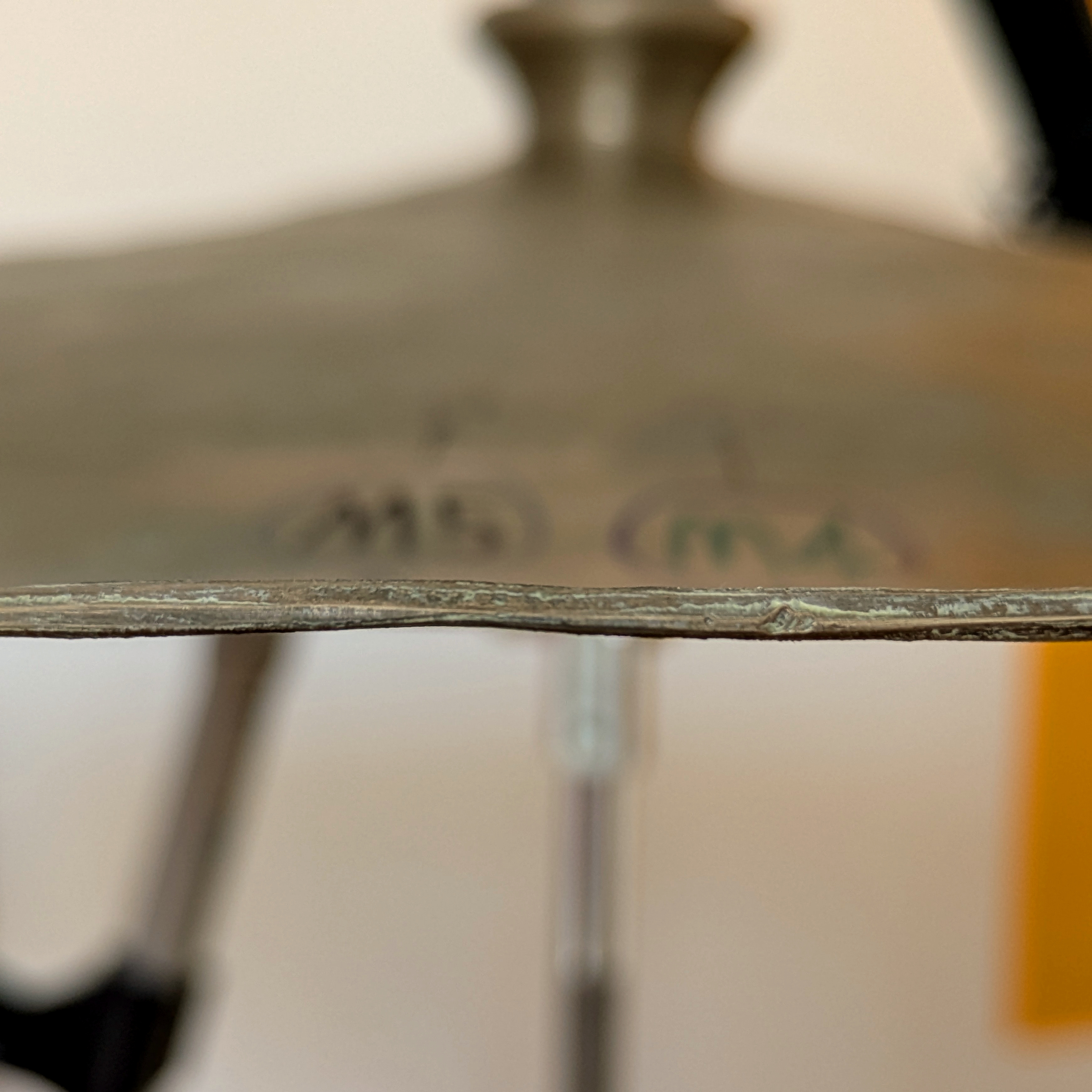

Pic 3 - An irregular rim is your friend

Pic 4 - Upside down flat wing nut

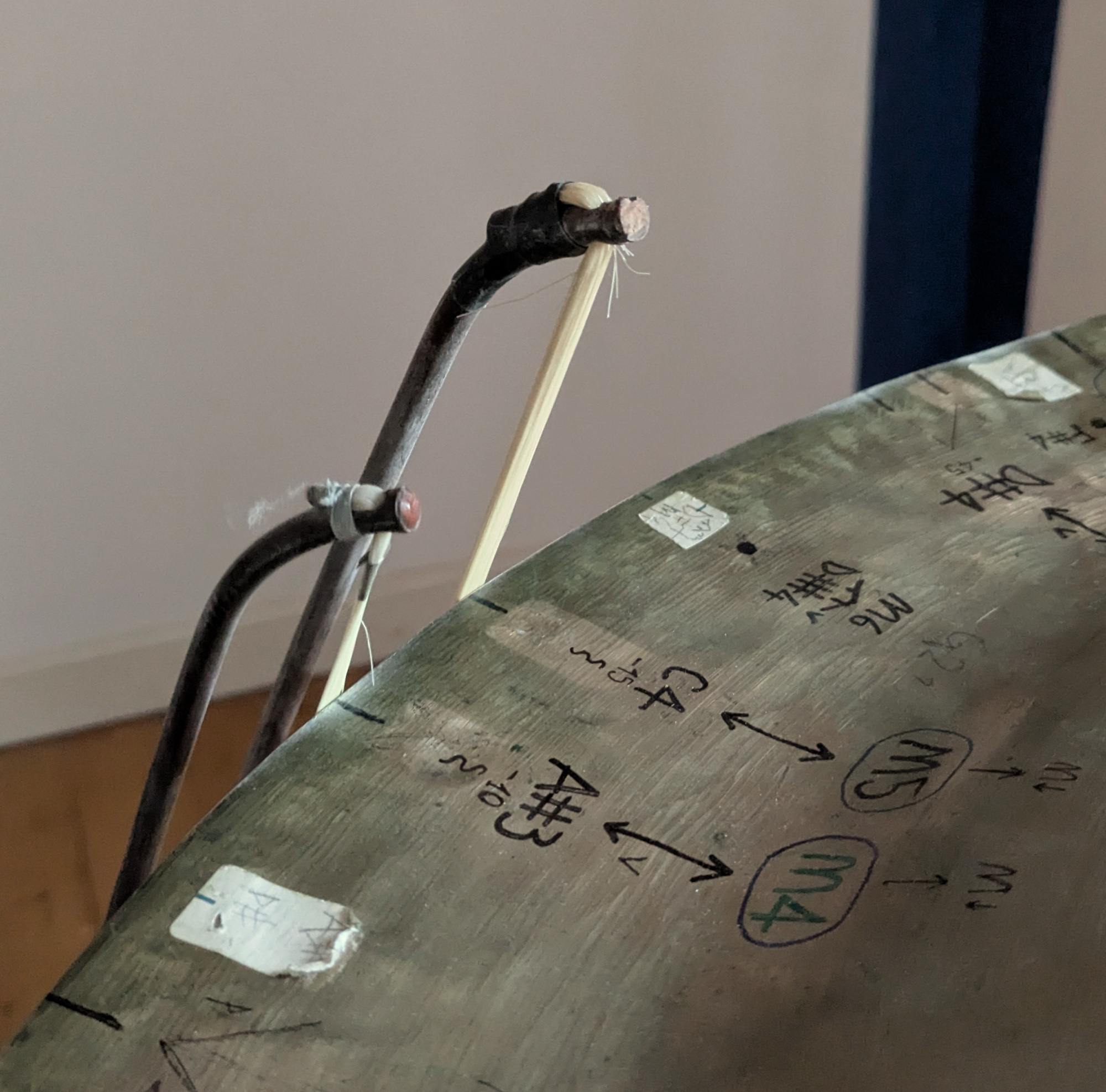

Pic 5 - An erhu bow with a spacer to keep the distance between the hair and the bow

For these reasons, all the techniques described below will behave differently on other cymbals, and the differences can become even more pronounced as their shapes vary.

Large cymbals and gongs often have an exceptionally rich response to the stroke of a bow. When they feature irregularities—as in large Wuhan cymbals shaped by hammering—and when set up properly, it is also possible to define many sounds with consistency. Standard straight cymbal stands can be used for this purpose, but they must be heavy enough not to tip over when lateral pressure is applied to the rim with the bow. The cymbals should be secured firmly on the stand, with one or more felt cushions placed both below and above the bell to allow them to vibrate. A useful trick is to screw a flat wing nut upside-down (pic. 4).

Tightening the cymbal generally reduces the complexity of the sound but gives more control over its behavior. When the cymbal is left completely loose by removing the wing nut, the resonances become richer, but the mapping becomes less consistent and fewer recurrent sounds can be found. Conversely, if the wing nut is too tight or the felt insufficient, the vibrations are overly dampened, and the resulting timbre is less interesting. With the right amount of tightness, the behavior remains complex, but it becomes possible to map many recurrences.

Regarding the bow, it takes more energy to bow a piece of metal than a string, requires more rosin, and causes the hair to break more easily. As an inexpensive solution, I use an erhu bow with a spacer inserted near the handle to maintain the distance between the hair and the stick (pic. 5). I keep the spacer in place by wrapping it with rubber bands. Many other solutions are possible, ranging from cello bows to custom-made ones3. Fishing line is also sometimes used because of its durability, but it produces a different set of sounds and is not suitable for this kind of mapping.

The sound changes according to the speed of the stroke, the pressure applied, the damping of a specific spot near the rim with the thumb or another object (a technique used to elicit the high register), and the position of the bow along the rim. Among these, the position on the circumference is the most important: all other parameters become repeatable only when anchored to a specific spot, and a shift of even one centimeter can completely alter the sound. In this sense, mapping these spots is a kind of physical measurement of the surface—or rather, a measurement of space guided by sound. With no visual markers, the only way I know to locate them is through attentive listening and careful identification of acoustic recurrences.

The behavior of each spot not only varies with the parameters mentioned above, but can also evolve over time under the same sustained action. A classic example is repeatedly bowing with the same stroke before the cymbal has time to stop vibrating: the accumulated vibration increases the volume, and many spots have their own volume thresholds after which multiphonics begin to appear.

The level of predictability varies from spot to spot. Changing position before the cymbal stops vibrating often alters the response, since the new energy interacts with the existing resonance and the behavior can become unpredictable, or lead to a recurrence unrelated to either of the initial spots (more about this in the 2-bows processes section). This effect is more pronounced when spots lie close to one another on the rim and when the volume is high, as the vibrations are more firmly established. Under ideal conditions it would probably be possible to map all the acoustic behaviors of a cymbal with certainty—or at least very closely—but these conditions are far from those in which I usually work. And in practice, the unstable behavior of some spots can become a strength rather than a limitation.

For the analysis I relied primarily on my ears and a tuning app to measure deviations in cents from a reference pitch, using computer-based spectral analysis only when finer precision was necessary.

Some spots respond in a completely predictable way and require no special attention to the stroke. Others are predictable only when played with a very specific gesture (high pressure, fast bowing, starting from silence, etc.). Most practical issues in performance concern obtaining the desired sound at the attack and then shaping its development. For this reason, the attack phase is crucial. Once the desired resonance is established with the right stroke, sustaining it is usually the easy part.

To sustain a sound with a single bow, it is helpful to slightly relieve the pressure at the end of each stroke so the cymbal continues to ring, and to begin the next stroke without damping the existing resonance. The duration of this pressure release should be minimized until the break between strokes becomes imperceptible. Hiding the break is easy with long-resonating sounds, but almost impossible with drier ones, especially some high-register pitches, where the discontinuity becomes audible—much like a bow change on a string instrument. A solid sustain is particularly useful for continuous dynamics such as turning a pitch into a multiphonic or a steady crescendo; however, for a crescendo, the spot where one bows is again crucial, since the available loudness range can vary significantly from one spot to another.

Finding the spots where a sound can be reproduced consistently takes time. When I began the mapping, I first made provisional marks with a pencil, then added paper labels to the spots that seemed more reliable and practiced with them regularly. When repeated playing confirmed that a spot was stable, I removed the paper and marked it permanently with a marker. For multiphonics, I use an “M” followed by a rising number, but I abandoned the idea of numbering them in order along the rim: from time to time a new one will inevitably appear, and renumbering everything would be impossible. Below you can see how many additional details have emerged on the same cymbal since its first mapping in 2010.

Pic 6a - 2010, first mapping on the lawn in front of the CCM at Mills College

Pic 6b - 2025, last mapping in Bristol

A classification of sounds and techniques

This is a tentative classification of the sounds and the techniques used to elicit them. Like most classifications, it’s simply a practical compromise for communicating within a group, for writing music, or for learning, and the categories often overlap. For instance, the distinction between a pitch and a multiphonic can be blurry: few pitches are perceived as pure, and in a multiphonic a single partial may dominate and be perceived as a fundamental. Similarly, a pitch produced at one spot may be higher than a sound produced elsewhere using the technique associated with the high register. In this framework, the line between pitch and multiphonic is based on acoustic quality, even though deciding when partials are prominent enough to count as a multiphonic is somewhat arbitrary. The high register is defined solely by the technique used, while the category of process is based solely on the acoustic behavior: once a recurrence is identified, the technique may need to be adjusted from case to case to achieve the desired development.

1) Pitches

Establishing the pitches is a good starting point to map the spots on a cymbal because they are the easiest to define. Bowing in different spots of an irregular cymbal will result in the discovery of different pitches. This is a melody played with some pitches found on three cymbals using two bows for the overlaps.

Every cymbal has a range where most of the stable pitches are, but exceptions are frequent, so it is frequent to come across isolated pitches that differ from the average of the others. This G5-46cents is one of the highest I found without using the specific technique for the higher register

This d#2 - 30c is one of the lowest I could repeat consistently.

There seem to be a relationship between this range and the diameter. On my 27″ cymbals, there is a concentration of stable pitches between G♯3 (415.30 Hz) and A♯3 (466.16 Hz), with many intermediate pitches that form microtonal intervals. The quality of these same pitches can also vary significantly from cymbal to cymbal.

2) Multiphonics

I use the term multiphonic in analogy with wind instruments: a sound containing more than one pitch, or a sound in which additional partials, harmonic or inharmonic, can emerge on top of an initially stable pitch. Generally, it is possible to define several spots on the same cymbal, associable with different multiphonics, with their distinctive character and inner movement. Some spots produce only multiphonics, no matter how they are bowed.

Most spots, however, start from a single pitch, and by adjusting bow pressure and/or volume (and occasionally bow speed), you can gradually reach the multiphonic.

Keep in mind that bow pressure and volume are not necessarily correlated. Every spot allows you to increase volume by accumulating strokes and building up vibration, but the most effective parameter varies from spot to spot: sometimes it’s easier to reach the multiphonic by applying more pressure, sometimes by bowing faster, and sometimes simply by repeating the same stroke before the previous vibration fades. In addition to this, the amount of volume required to activate a multiphonic can differ wildly—some spots unlock their multiphonic at very low dynamics, especially the ones responsive to pressure, while others demand extreme loudness and can become surprisingly, even painfully, loud.

A standard situation is a pitch that becomes louder and then “breaks”, sometimes only at extremely high dynamic levels.

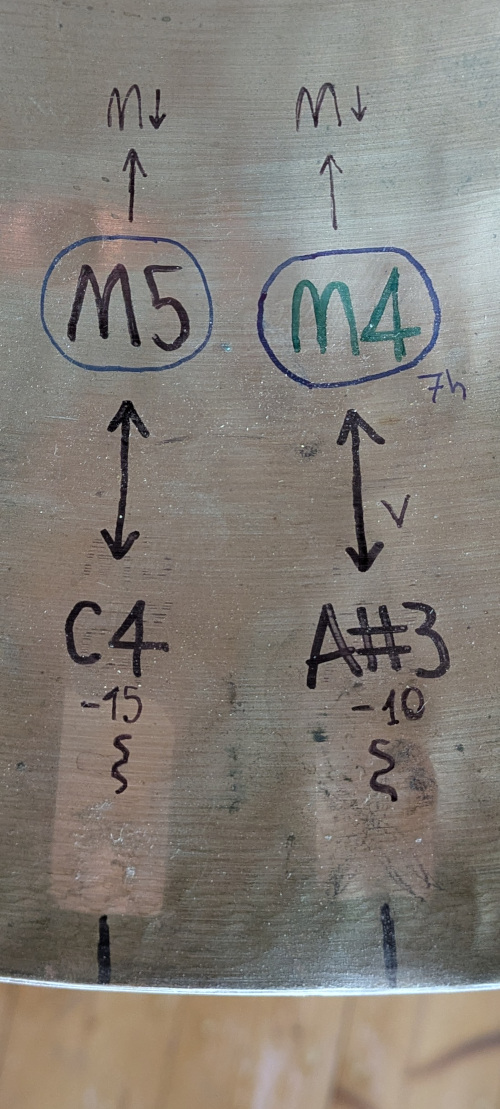

Pic 7: multiphonic marks

On my multiphonic marks (pic. 7), arrows drawn next to certain spots indicate how each spot responds to changes in bowing parameters. Certain transitions are reversible, but most are not. I mark reversible ones with double-headed arrows (↔) and irreversible ones with single arrows (→). A common irreversible process occurs when the sound collapses toward the low frequencies (M↓) due to high pressure or high volume. At this point, returning to the initial state of the resonance requires either stopping the cymbal completely or gently damping the spot near the rim with the thumb or a soft object while bowing. I see analogies between this behaviour and audio feedback.

Most arrows point from a pitch to a numbered multiphonic on the same spot, but some indicate more complex paths, including multiple spots or intermediate states (more bout this in the process sections). I add “v” for multiphonics primarily reached by increasing volume, and “p” for those reached by adjusting bow pressure. The multiphonics responsive to pressure are especially useful because allow for transitions keeping the volume at reasonably stable dynamics.

As with wind instruments, it is also possible to distinguish between standard multiphonics and beating multiphonics.

Most multiphonics contain inharmonic partials, but occasionally the added components form a surprisingly harmonic structure. These added harmonics may appear below the initial pitch, above it, or distributed on both sides.

Some cases are particularly striking. In this example, the pitch produced by bowing is A♯3 −10¢ (~464 Hz), but as soon as I increase the volume and the harmonic multiphonic appears, it introduces a fundamental at ~133 Hz and its corresponding harmonic series. The ~266 Hz harmonic is the strongest, recontextualising the original pitch as an almost perfect harmonic 7th (7/4). In the third wave I apply heavy bow pressure, breaking the harmonic structure; the multiphonic collapses irreversibly into a lower register. For this example I include the spectrogram, where the three harmonic waves are clearly visible and the original pitch appears “embedded” among the harmonics of the previously hidden fundamental.

Pic 8: A#3-10c to harmonic multiphonic - spectrum

Occasionally, multiphonic spots behave differently depending on bow direction. In rare cases the difference between up-stroke and down-stroke is so clear that the two gestures produce a perceivable harmonic “melody.”

I liked its sudden attack and dual stability so much that I wrote the end of this work around it (from about 16:00).

Some spots remain unpredictable even now, and I still cannot reliably control them, but they can be a lot of fun nonetheless.

3) High register

Pic 9: high register pitches

To produce a pitch in the high register, it is enough to apply pressure on the cymbal with a finger at about 2.5cm or less from the rim, in the same position as the bow or close.

The closer the pressure point is to the rim, the higher the pitch. However, this is only a general principle, and there are plenty of exceptions. Some spots produce louder high pitches, others never rise very high, and some simply do not alter the initial pitch at all. Generally, multiphonic spots favor high pitches, and it is possible to map them precisely—though even a minute positional change on the order of millimeters, or a change in the object used to apply pressure, can render this distinction irrelevant.

Moving the thumb (or object) along a line from the bow toward the center of the cymbal—especially within the sensitive area—can produce jumps and transitions between high pitches, analogous to harmonics on a string but without the same harmonic precision and often without the same predictability.

In the example below, I shift the damping point on a multiphonic spot, often by extremely small distances, especially for the highest pitches (on the order of millimeters). When the low sound appears, it is because I briefly remove my thumb and let the cymbal vibrate in its standard multiphonic state before damping again. At the end, I remove my thumb entirely and let the normal sound emerge and gradually replace the high pitch obtained with this technique.

4) Processes

Analogously to what I described earlier for multiphonics, I use arrows to indicate any repeatable transitions between different types of sounds. I call these transitions processes. Many multiphonics occur only when starting from a pitch, as shown in the examples in the multiphonic section. So, most of the arrows go from a pitch to a numbered multiphonic on the same spot, but processes involving multiple stages are also common.

It is always possible to recognize subtle changes within a multiphonic, and occasionally these can be controlled, but I consider those part of the character of the multiphonic itself.

In this example, I start from the G5–46 cents obtained with standard bowing (as presented in the pitches section), then apply bow pressure until it becomes a multiphonic, and finally, through a combination of volume and additional pressure, collapse the sound toward the low register. This process is irreversible: the only way to return to the starting point is by damping the rim area. Applying pressure gently with the thumb while bowing can smooth the transition to the starting pitch.

Here, I start from the G#3, with increasingly stronger bow strokes I introduce a lower double octave and then everything collapsed to a multiphinc

Pic 10: 2-spot process

Processes involving more than one spot with a single bow, switching locations on the same cymbal before the vibration has time to fade, are possible, though difficult to define in a consistent way. They tend to become complex quickly (see pic. 10), since each transition depends not only on the gesture but on the current state of the cymbal’s resonance. Yet because of this complex vibrations, they often reveal unexpectedly rich and satisfying sounds.

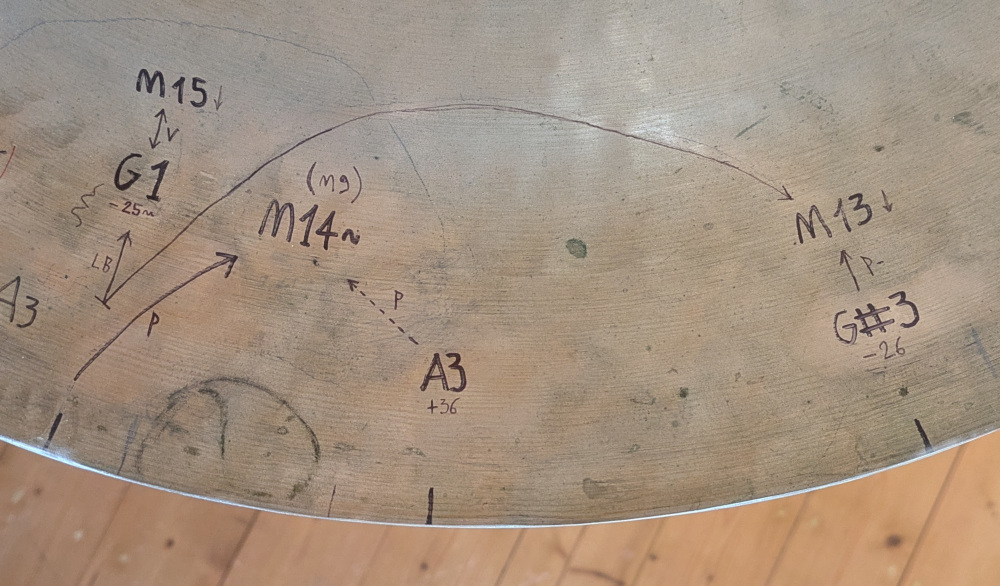

In the example below, I move from G♯3 − 26¢ to a multiphonic spot I marked as multiphonic 14 (M14). But its behaviour when approached from G♯3 − 26¢ is completely different from how it behaves when starting from a stopped cymbal, and from this state it falls into one of the lowest pitches I can reliably reproduce, a G1 − ~25¢. I call these rebound spots. I repeat the sequence twice to show how reliably the same result can be reached. In the second pass, I end with a swelling in volume, which adds higher partials to the low drone.

In this work, during the first ten minutes all the microtonal changes come from shifting between a few spots on the same cymbal without damping. I use two bows mainly to switch spots more quickly, but there is very little simultaneous bowing. Reaching the point where the bow strokes behaved exactly as they do in the recording required a great deal of trial and error, and reproducing the improvisation exactly would be difficult. However, once (and if) the initial sound is established, the microtonal variations and processes become controllable.

5) Tails

When you release pressure after a bow stroke, the tail of the sound is usually long and gets always smaller - think of the tail a mouse. Just the same pitch or multiphonic with a long release.

However, on a few spots, the tail opens up after releasing the pressure, and you've got a magnificent peacock! I repeat the stroke a few times to demonstrate how consistent these curious shapes can be, especially when starting from a stopped or nearly stopped cymbal.

6) 2 bows processes, chords, and just intonation (if you're lucky...)

Pic 11: 2 bows on the same cymbal, opposed spots

Pic 12: 2 bows on close spots

Using two bows has the obvious advantage of allowing two parts on two different cymbals, and when the transition to a multiphonic depends on pressure or volume, it becomes possible to control two independent processes simultaneously with two arms. But focusing both bows on the same cymbal also has its strengths.

For instance, bowing two pitch spots on the same cymbal will often produce a new multiphonic rather than a simple two-note chord. Diametrically opposed spots are especially prone to behave this way: the pitches tend to fade into one another, with a multiphonic forming in the transition, and it is possible to move back and forth between them by reducing the volume on one spot or the other (pic. 11).

In this example (literally what I am playing in the picture), I start from a G# +12¢ and create three swellings with a C –48¢, which lies almost diametrically opposite on the rim. The interval is a very unjust third (~340¢): approximately between a just minor third (6/5 ~315¢) and a just major third (5/4 ~386¢). On top of this unstable chord, additional partials can be heard, produced by the interaction between the two bowing spots.

Here I start again from the same G# +12¢ and bow another almost diametrically opposed spot, producing an A# +20¢. Instead of returning to the first pitch after the multiphonic overlap, I continue bowing only the diametrically opposed spot and remain on the second pitch. As before, the overlapping transition is completely reversible: it is possible to move gradually between the two pitches, and the multiphonic effects during the overlap are even more pronounced.

However, when the spots are closer together (pic. 12), this predictable behavior becomes less likely. In the example below, I use two adjacent spots, A♯3 − 10¢ and C4 − 15¢, both with multiphonic possibilities with a single bow. I start playng them separately with one bow, then I sustain A♯3 − 10¢ and with the second bow, I introduce waves by bowing C4 − 15¢. The first wave is very quiet and works as with the examples before, reversible, with the multiphonic transition. But as soon as the wave gets only a little louder the sound collapses into a completely different low drone, unrelated to the initial pair. I repeat the process again with more energy and the internal movement of the sound changes again into something I cannot repeat consistently - altough, this is not always the case and many of these transitions are repeatable.

Just-tuned intervals are rare, but an absolute marvel when you find the spots. Below I start from a G♯3 + 1¢ spot and slowly begin bowing a second spot on C4 − 17¢. The second spot lies about 45° to the left of the first, and in this case the two form a fully reversible pair. A just major third is 386¢, which is 14¢ flat from the equal-tempered one. Here the difference is 18¢, but 4¢ is well within perceptual tolerance, and the upper harmonics ring clearly. As an arbitrary rule of thumb, I accept a tolerance of ±5¢ (one-twentieth of a semitone) when considering an interval “just-tuned.”

And if such spots happen to lie on two different cymbals, they have the possibility to add a lower fifth to the initial pitch with a single bow, and then, by increasing pressure, shift into a less harmonic multiphonic, then that might be one of the most joyful discoveries I can imagine. With just a couple of these pairs, I could play for half an hour without ever getting bored.

Complex examples on specific areas

Pic 13: detail of the mapping

Two bows on the same cymbal. I start from from G#3 on the left and I itroduce the just major third with C4 - 17c, like in the 2-bow process example x, but this time I land on the C4 and only then I go bak to the G, when the G is stable again, I start applying more pressure with a single bow and I move to the multiphonic (M7). I then go back and start bowing with more energy to let the lower octave come out.

Pic 14: detail of the mapping

One bow plus a finger for damping. I start from A♯3 + 37¢ and introduce the lower fifth by bowing faster. Then I play a small harmonic oddity by bowing A3 + 12¢ using the high-register technique, damping on the point marked with a dot. I alternate between these two spots for a moment. After that, I play the double-stroke multiphonic from the earlier example, and I finish by repeating the harmonic movement on the A3 + 12¢ spot.

Pic 15: detail of the mapping

This last example shows how far it is possible to go in the process of discovery—almost like solving a puzzle. Everything is played with one bow and without damping, so the entire sequence can be performed with a single arm. I begin by oscillating between A3 + 10¢ and B3 + 38¢, two close spots that have an unusually stable behaviour even without damping. As I play louder, harmonics begin to emerge on top of the oscillation. Then I reverse the process and return to A3 + 10¢. From here, I start the puzzle that leads to multiphonic 10 (M10): I increase the pressure and arrive at M3; at that point the safest way to reach C♯3 + 10¢ is to bow the B3 + 38¢ spot, which, when approached from M3, behaves completely differently from how it responds when starting from silence, and it leads reliably to a stable C♯3. M10 can be reached only from this pitch by further increasing pressure, and it is irreversible. Afterward, I move to the area on the left. I start from G♯3 − 12¢ and transition to G♯3 + 15¢ without stopping the cymbal. As before, the behaviour is completely different from what happens when starting from a stopped cymbal, and from this state I access M7. Then I return to G♯3 − 12¢ and reach M8 by increasing pressure. You can hear how M8 is very different in character from M7, and it is also fully reversible, so I can return easily to G♯ − 12¢ without lowering the vibration, and then move again to M7. This time, increasing the pressure further leads to the irreversible low-register collapse (M↓).

Footnotes

(1) Unfortunately, I had to remove the Wikipedia link to Eddie Prévost, as the page was

clearly written by friends of the subject — and was rightly flagged for that reason.

I also had to remove the AMM page. I don’t know the authors,

but as soon as I looked at it again, one detail caught my eye:

the release date of their first album is listed as 1966, but if you check the Elektra catalogue,

it’s clearly 1967 (EUKS 7256). This may seem like a small detail, but it’s hard to believe it’s accidental,

especially since elsewhere it’s claimed that they were the first, alongside Nuova Consonanza,

to release an album of free improvisation, and elsewhere again that they were simply the first.

That’s not accurate: even considering only the well-known examples,

Roscoe Mitchell’s Sound was released in 1966 on Delmark, and Milford Graves' Percussion Ensemble

was recorded in 1965 and released in 66 on ESP-Disk.

Even within the European context, the claim doesn’t hold up,

since Nuova Consonanza released Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza in 1966 on RCA. By the same logic, Musica Elettronica Viva’s first release, Spacecraft (1971), would also need to be retrodated, since much of its material derives from performances and recordings made between 1966 and 1967.

(2) See how Gino Robair cuts standard cymbals to make them irregular.

(3) See the custom bows made by Tatsuya Nakatani.